All facets of training whether you are a runner, triathlete, tennis player, crossfitter, or weekend warrior have a dependency on diet. As medical technology continues to increase the ability to test for different components of our blood, tissue and muscles the evolution of new diet trends will continue.

As an endurance athlete I have depended on Nutrition timing during training and long events, but recently I have been doing some experimenting. The question I have: when does timing of nutrition make sense and how so.

I recently went out for a 12 mile run with a friend and did so with only my daily regimen of vitamins and such. Usually, I would be packed with gels, electrolytes and water, but this time I was armed with only the water fountains on the course. I was shocked when we finished 12.5 miles and I felt fine. I continued to be mindful when I realized that even afterward I didn’t feel the effects of this long run like I usually would.

It is true, that I continue to benefit from my Ironman training from last year, as I continue to maintain at least my long runs. However, I usually would always prepare for runs over 6 miles with, what I thought was the appropriate nutrition. I am now questioning that especially after doing some more research.

Nutrient timing simply means eating specific nutrients (such as protein or carbs)… in specific amounts… at specific times (such as before, during, or after exercise).

In the early 2000s, with the publication of Nutrient Timing: The Future of Sports Nutrition by Drs. John Ivy and Robert Portman, the trend of all following publications became Nutrition Timing.

Since then, there have been discoveries that some of those early studies had design flaws or weaknesses.

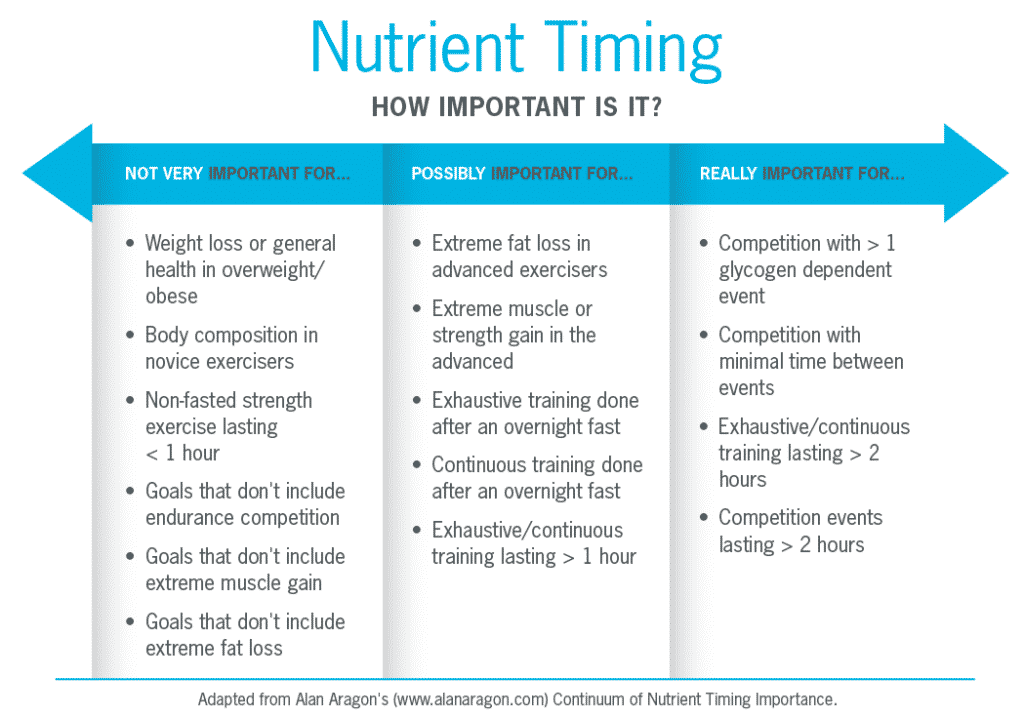

Interestingly, as more long-term data appeared, nutrient timing started to seem like less of a universal solution. Sure, there were still strong indications that it could be useful and important in certain scenarios.

Unfortunately very few people talk about the flip side: Further research, using similar protocols, failed to find the same effect. See what I mean about new technology dictating new results?

For example, most of us have heard the Holy Grail of nutrient timing research has been something we call the post-workout “anabolic window of opportunity.”

The basic idea is that after exercise, especially within the first 30-45 minutes or so, our bodies are greedy for nutrients.

In theory, movement — especially intense movement, such as weight training or sprint intervals — turns our bodies into nutrient-processing powerhouses.

During this time our muscles suck in glucose hungrily, either oxidizing it as fuel or more readily storing it as glycogen (instead of fat). And post-workout protein consumption cranks up protein synthesis.

In fact, one study even showed that waiting longer than 45 minutes after exercise for a meal would significantly diminish the benefits of training.

With these physiological details in people’s minds, it became gospel that we should consume a fast-digesting protein and carbohydrate drink the minute our training ended.

Or, even better, immediately before training.

The only problem: research supporting this idea was short-term.

And just because we see positive effects in the short-term (like, in the next half-hour) doesn’t mean these effects will contribute to long-term results (like, in 3 months).

In fact, recent longer-term studies, as well as two incredibly thorough reviews, indicate that the “anabolic window of opportunity” is actually a whole lot bigger than we used to believe.

It’s no longer like the 1 inch cellphone screen that you practically have to squint to see. It’s a huge, smartphone like LCD screen.

This is just one of the areas that have been re-researched with new technology. To keep this post as short as possible below are some other aspects of nutrition timing I have found.

Are you a proponent of Nutrient Timing and what is your schedule like?

Carpe Vitam!

–IronGoof